|

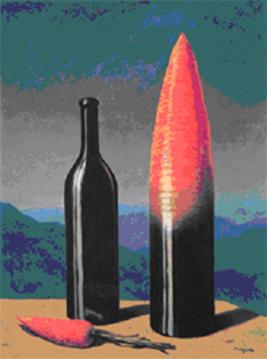

David Byrne, courtesy of WikiPedia

(which destroyed encyclopedias) |

Some days, I feel like I just write the same articles over and over. Sisyphus pushing the rock, defending streaming services. If it's not some random person on the internet, it's

Thom Yorke.

Now here comes white-haired David Byrne, shuffling down the sidewalk, yelling about the good old days and the end of the music world.

Byrne was the leader of

Talking Heads, one of those moderately successful bands that manages to become influential and is a part of the undisputed "canon of cool" for many musicians. Like with Thom Yorke, it stings a little for me to hear musicians I respect and who influenced me speaking out against my work - work that I have engaged in for their benefit.

Evil?

Byrne asks "Are these services evil?" It's difficult not to respond with something equally churlish and provocative, like "Is David Byrne stupid, or just ignorant?" Probably the latter, as he admits and then demonstrates a lack of detailed knowledge about how the services work.

Still, I am compelled to respond to these uninformed and incorrect assertions.

All Internet services are not the same. Byrne lumps streaming services in with YouTube and Pandora, which is sort of like lumping your bank in with muggers and vending machines. "Well, sure, they're kinda different, but they all take your money, right?"

Byrne asks if streaming services are "simply a legalized version of file-sharing sites such as Napster and Pirate Bay". Nope, at least not in terms of infrastructure and effort. Napster and Pirate Bay don't ingest and host terabytes of music and push it out to CDNs worldwide. They don't provide customer support. I could go on.

The most important distinction is this: YouTube and Pandora don't need or get permission to offer the music they deliver. Streaming services have to get permission from the artist, label, and publisher. And then they pay huge guarantees and submit to a ton of control from the content owners.

It's streaming or nothing. Byrne repeats the assertion that no one will buy CDs or pay for downloads when streaming is available. But there's literally years of research that show that the most avid streamers still buy music, and buy more music, than people who don't stream. Put another way, for every Spotify user who says "I'll never buy a CD again", I'll show you a Rhapsody user who says "I'm buying more music than ever". Streaming increases sales.

But why would you buy when you can stream? Well, maybe you're trying to give the artist you like more money. Maybe you want a copy to keep. People do it.

Monopoly...someday. Byrne asserts that we'll end up with a monopoly, and that will be very bad. Well, it's been 12 years, and we don't have a monopoly. We have a bunch of struggling services, and tons of competition in most of the major music markets. The USA (the biggest music market in the world) alone has at least a half-dozen streaming services. And Apple and Amazon haven't even entered the market...yet.

Griping about payment size. I've gone into this many, many times. It is true that for some artists, the per-stream payment has been low. That has a lot to do with the artist's deal with the labels. I will also again point out the labels are collecting money from services even when users play nothing. Is any of that money going to the artist? If not, the artist should be talking to their label. And I repeat my favorite question: What payment would you suggest for a single stream?

Go browse a store instead. Byrne says you could just go to Bandcamp instead. Yeah, Bandcamp. A place that has none of the content. Where the artist doesn't get paid at all when it's played. Look, I like Bandcamp.

I have some of my music available there. But it is not a good substitute for subscription services for the reasons above. It's more like iTunes, but more fair. Amazon is pretty much the same. And most bands on major labels aren't allowed to put their content on Bandcamp.

People only go to these places when they have already decided to buy something. It is a very different experience.

It's totally true that the purchase links in Spotify and other services are lame. They're in there because the record labels make us put them in there, not because we think they're a good idea.

Great Pull Quote!

Byrne being the media old hand that he is, he closes with the usual "everything will collapse into these services and the poor artists will starve". The pull quote and tweeted memed headline is "the internet will suck the creative content out of the whole world until nothing is left."

Provocative! Exciting! Wrong!

In some ways, this is just an updated version of Sousa's "

The Menace of Mechanical Music". But let's look at a similar model: video.

Jack Valenti famously said that the VCR was the Hollywood Strangler. And instead, it grew revenues tremendously. Opened new markets. There are lots of people who subscribe to Netflix. They're also still watching broadcast or cable, going to movies, buying and renting movies on DVD and Blu-Ray and as digital files, watching pay-per-view, and watching free internet video as well.

New methods of enjoying art bring more consumption of art in more areas.

If that wasn't true, then Sousa would have been right, and the dawn of recording would have destroyed music such that people like David Byrne and Thom Yorke would never have had careers writing and performing it.

Look at ebooks.

People are buying and reading more books than ever.

It's depressing to keep arguing these points. But there is some hope.

Dave Allen (of Gang of Four and Shriekback) has finally come around.

His excellent response is well worth a read, and I'll repeat many of his points here. Mr. Allen and I have discussed these issues in the past, and haven't always seen eye to eye. But he brings some welcome perspective. Some of his strong points:

There aren't enough good rebuttals. The Guardian will print things that Yorke and Byrne say because they're both famous musicians, and their tirades will sell papers. It would be nice for a change to see them either allow someone from the industry to respond, or find another famous musician who will say something positive about these services. In the meantime, I'll keep plugging away.

The old system was as bad or worse. As per usual, people start trotting out how many streams a musician has to generate to make minimum wage, and start comparing it to selling t-shirts or CDs. I will again point out that it requires nearly no effort or upfront cost on the part of the

musician to provide that stream - that's the work the service is doing: ingesting content, making it available worldwide, writing client software, and more.

Compare that to lugging t-shirts and CDs around, carrying change, and soliciting transactions. That's why you get to keep more money in those scenarios: you're doing more work, you're carrying inventory.

Making a living by selling CDs is as hard or harder. Fine, ignore the previous points. Focus on the actual statistics:

- There were more than 98,000 new albums released in 2009.

- Of those 98,000 albums, about 2% sold more than 5,000 copies.

- About 1% sold more than 10,000 copies.

- As far back as the mid-/late-90s, the average band on a major label with a national promo push would sell about 1,000 albums

And all those new records are competing with Led Zeppelin IV and OK Computer and Speaking In Tongues.

If you think selling CDs is going to make you more money, you're wrong. Statistically, you're not even making minimum wage.

The current internet alternatives to streaming are so much worse. Spotify, Rhapsody, MOG, and other services are paying out 70-80% of their gross income directly to "content owners": record labels, publishers, and yes, artists. iTunes pays 70%. Other internet alternatives like YouTube and 8Tracks pay nothing, and only achieved their current success by either operating illegally (in a "get big, then get licensed and legit" model) or by exploiting a loophole in the DMCA.

Those royalties are cripplingly high. Spotify still isn't profitable. Most of the streaming services are money-losers. Even mighty iTunes just breaks even. These services cannot pay any more than they are already paying...and frankly, shouldn't have to just because artists signed deals with labels which the artist now regrets.

Listeners won't pay more. I've done the customer research many times. The primary reason people don't use these services? Too expensive. And when the free services bloat up with ads, customers turn away and go back to unlicensed services or illegal downloading. Or don't bother playing music at all.

I'll conclude with noting that

Messrs. Byrne and Yorke aren't helping the music business, they're hurting it. It's difficult for today's listeners to understand the distinction between legitimate services and piracy, between what pays the artist and what doesn't. And when they attack the services that are doing the right thing, they are sending a message to those listeners that sounds like "you might as well just steal all the music you want, because the artist doesn't get paid anyway." Again, I've done the market research. I've heard it from the music fans

I suppose this constant criticism is a sign of the legitimacy of streaming services, but it sure doesn't feel like a "win".

Life Is Hard

Byrne closes with an appeal that sounds a bit like "won't someone please think of the children???" He notes that life is hard for up-and-coming musicians, and that even talented ones may have to give up if they can't find a way to make a living...and that the future of musical culture thus "looks grim".

OK, three more points and I'm out.

1. It has never been easy to be an up-and-coming musician. It wasn't easy when Byrne was coming up (there are plenty of his peers that never made it big like he did). It wasn't easy when Sousa was coming up, either.

As I noted previously, there were 98,000 albums released in 2009. Recent years have had similar numbers.

That means all those up-and-coming artists have a lot of competition - not only from all the other 199,999 albums released that weren't theirs, but from all the great old records released over the last 50 years, like those by David Byrne and Thom Yorke. It is not an easy job. It never has been. And streaming services aren't making it any worse. If anything, they're offering an easy, low-cost way to make music available worldwide.

2. 98,000 albums. That's a lot of new music, and those numbers keep going up. So even after over a decade of streaming music services, the number of new albums being created continues to rise. If there is some kind of creative apocalypse, it hasn't happened yet. I'd argue we're seeing the opposite - massive growth in content creation.

I also hope Byrne isn't so commerce-minded that he can't see that many

artists (as opposed to

entertainers) create because they have to, not because it's a good career choice.

3. Look up what "amateur" means. A personal anecdote: I was an aspiring professional musician. I dipped my toe in nearly every part of the music business before Napster came along. It was really hard. And I came to realize that even being talented wasn't enough. You had to be talented and lucky.

That wasn't good enough for me, so

I got a day job (making streaming services, it turned out).

I still write, perform, and record music. I distribute it worldwide. I don't do it for the money, I do it for the love of music. I am not unique.

I do not consider myself a "great artist", but I am pretty sure most of the folks I do consider great artists create because they love creating first, and because they can get paid second.

It is entirely possible that subscription music is a terrible idea, and one that will become a footnote in history, like the 8-track cassette. But I have a feeling that if it were to vanish, many artists and music lovers would mourn its loss and sing its praises.

That may sound hard to believe, but then who'd have thought David Byrne would be arguing in favor of the past and fighting against the future?