Even before the UCP was issued to soldiers, lab tests showed that it didn't perform as well as other designs. But the Army's textile researchers now say that military brass had already made up their minds in favor of the new-fangled pixelated look.Metafilter covered it this morning:

After spending $5 billion dollars to develop the Universal Camouflage Pattern (UCP), the US Army is abandoning the grey-green pixelated camouflage because it has routinely failed to hide soldiers from view in nearly every environment it has been tried in, and considers adopting the UCP "a colossal mistake" and a "fiasco".While it is worth reading these articles yourself, a brief summary is that the Army spent a lot of money to develop a single camouflage pattern with the intent to both better protect their soldiers and save money. They've done neither. The process was terribly flawed and the resulting product terribly flawed.

A recurring theme in the comments for both articles was a stunned disbelief that an organization as large and well-funded as the United States Army would have made such a big decision without lots of rigorous science, testing, and other safeguards to guarantee things would work, and that they would fail so spectacularly.

Blizzard Entertainment is one of the biggest video game companies in the world. These days they're mostly known for the massively multiplayer online role-playing game "World of Warcraft".

But prior to WOW, they released 2 "action RPGs", Diablo and Diablo 2. Both featured a kind of Skinner box-simple game play combined with a casino-style partial reinforcement reward system. In other words, the games were stupid simple to "play" and very compelling, scratching a gambler's itch.

Diablo 2 was extremely successful. It was also released in 2000, which is about a million years ago in the gaming world. Given how much money it made, another installment in the series was inevitable.

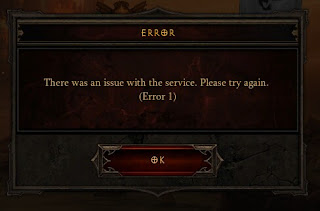

Diablo 3 was launched about a month ago. It has suffered from serious technical problems that have prevented gamers from playing at all, seriously crippled the game experience for users, and, most disappointingly, they've already been hacked.

The hacking is a sore point for Blizzard because Diablo 3 requires a constant internet connection in order to play. This is a big change from previous Diablo installments (and most games in general). It's somewhat akin to Microsoft Word requiring you to be online - and Microsoft's servers to be up and running - in order for you to write a document.

For many players, that's a deal-breaker, and the game has been pilloried by a certain portion of the gamer world as a result. That Blizzard has failed to keep up their end - not only has the game been hacked, but it has not even been playable - seems to justify some of their outrage.

On top of all that, some reviews of the game are sour. The gist of it is "we waited 11 years for this?" Diablo 3 isn't an unqualified refinement. Some argue it further dumbs down already simplistic gameplay. Blizzard itself has been frantically patching and rebalancing the game - in effect, rewriting it as people are playing it, after it's "done".

In the intervening 11 years, there have been several other games that have jumped in to fill the void, and many critics argue these small independent productions are far better than Diablo 3.

Diablo 3 had dozens of people working on it (40-70 at various times). Din's Curse had about 3.

Blizzard put a large team with tons of cash on this project, and spent an extremely long time developing the game. I'm sure it will be a "success" due to extensive marketing, and unlike the camouflage, won't kill anyone (though Diablo 2 arguably did). But Diablo 3 is clearly not going to meet expectations.

How could this happen?

These days I also work for a big company, and I have a new perspective on the problems with big.

One problem is assuming that a "big" company or team means every part of every project gets lots of resources. In fact, what often happens is big companies have so many different elements and such wide scope that often, the "core" of the project ends up with less resourcing than a smaller company might provide it.

In the Army's case, perhaps they had too much bureaucracy and oversight, and not enough actual research and development. In Blizzard's case, perhaps a surfeit of marketing and art and a dearth of testing.

Larger teams are also much harder to manage and coordinate. Think about trying to go to lunch. If you go by yourself, it's trivial. You walk out the door, find a place, get your food, and you're done. Now imagine trying to go to lunch with 7 of your co-workers. Is everyone ready to go? Where are we going? How long is the line? Are we eating there?

It gets exponentially more difficult to complete the same task. Even harder if you're dealing with multiple locations and time zones. Then you factor in this kind of inefficiency or challenge daily, compounded by people taking vacation, being sick, and the usual variance in human productivity.

Another element is lack of authority. Big teams and organizations frequently have multiple levels of stakeholders. Everyone can say "no" and very few people can provide a definitive, can't-be-overruled-or-challenged-yes. And those that can provide that kind of authority are often so distant they cannot make a truly informed decision, and can't or won't see the results of their decision in action - much like a general continents away from the actual conflict.

How do you deal with all that? Some suggestions:

- Reduce scope. Ironically, often bigger teams mean you can do less, and what you can do takes longer. Think about going to lunch - you need more time, and your options are actually much smaller (accommodating vegetarians and more schedules).

- Many small milestones. Break your task or project into as many short, achievable, measurable goals as possible, and keep driving the team towards the next one. This makes it easy to measure progress and helps the team stay focused on "the next important thing". This also helps...

- Create a sense of urgency/Be ready to ship frequently. Don't spend 11 years on a project. Start with a 6 month deadline. At the end, look at what you could ship and decide whether it's good enough or if you want to commit more time to polish things up...then spend the next 6 months addressing those issues only. Without that sense of deadline, people will just keep spinning and iterating, showing up for work, doing stuff, and NOT driving for a solid release.

- Know how you measure success and completion. Everyone on the team should know what will make your project "done" and "good". Check work against these unchanging criteria regularly. This prevents mission drift and keeps everyone honest.

- Have a Project Leader close to the project. Make sure at least one person on the team is responsible (meaning accountability and authority) for whether or not your thing is any good/meets the original needs. If the organization cannot put that kind of trust in the project leader, it has fundamental problems that make success highly unlikely.

These are all things that "small" organizations do inherently. Think small!

2 comments:

This reminds me a little of when I met a famous indie rock band right before their first major-label release. A member was talking about how she thought that with all the new resources, better studio, etc that it would be a much better experience. Instead they made the same mistakes as before, only this time it cost more money.

Well put, Anu. Given that I am in my last week of working for "big," I can tell you that I have seen every issue you've mentioned. One more thing I'd add is transparency... Often there are forces at work in big companies that are outside of your project but will affect it nonetheless. Being upfront with the team about changes and politics will actually help keep a project on target.

Post a Comment