As I write this, it is the summer of 2020 -- the summer of the virus. It has been a negative space. Nothing. A zero. A time I have tried to fill with creativity and distraction. It has reminded me of another summer, 30 years in the past, the “zero summer” of 1990.

|

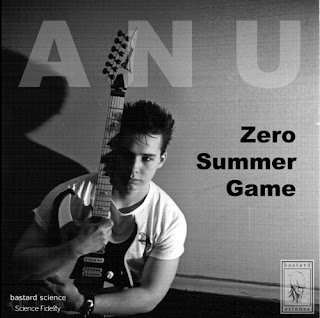

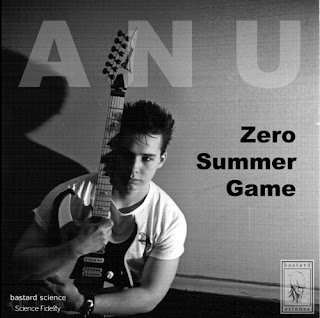

Album cover from the MP3.com re-issue.

Photo by Amanda Erlanson |

If we are defining “albums of influence” as records which changed my life, or how I thought about music, or meant something to me, or were memorable, or all of the above, then one album stands above all others in my life. My first solo album, written and recorded in the summer of 1990: "Zero Summer Game".

The summer of 1990 was special for me. In retrospect, it was one of the happiest times in my life.

In early June, I was home from college, between my junior and senior years. My parents were away for most of the season, traveling. My brother was at Outward Bound. I was in the house, alone.

The house was beautiful and spacious, set below and back from the private drive by a long and steep driveway. The backyard backed up to park land. The street fed into a small suburban neighborhood of mostly unpretentious homes.

What had been my bedroom was now my brother’s. What had been his room was now the “guest room”, redecorated, and that would be where I resided. It felt like a hotel suite, even after I had set up my stereo and unpacked my few bags. What little of my things remained were unceremoniously piled in the closet. I was now a guest in what had been my home.

The weather was typical for Northern Virginia summer: aggressively hot and humid. The skies would darken periodically, but the rain largely refused to provide relief.

After a few days of sleeping off my college fatigue and nights watching rented VHS tapes, one day I went to the basement library of the house. One wall was mostly windows, looking out onto the woods. It was a big room, mostly empty but for bookshelves, a table, and a place to sit and read -- and I set up my recording gear:

One night, after dinner, I went downstairs, flipped on the TV, and started noodling around on my guitar. Inspired by a music video, I started writing on a song of my own. I stayed up for hours working on it, programming drums, making a bass part, writing two guitar parts, lyrics, and lead and background vocals. Home alone, I felt uninhibited about singing loud and trying new things with my voice. I even put in a guitar solo. I went to bed around 3 am.

The next day, I rolled out of bed and hit play on the cassette deck in my room to listen to what I had done the night before. It was...good. I had written and recorded a good song. I wondered if I could do it again.

And so the “zero summer” of 1990 began.

Days, I would get up around 10 or 11. I didn’t drink coffee in those days. I’d let the dog out, and have water or juice. I’d microwave something -- oatmeal, eggs, a sausage biscuit. I would glance at the newspaper.

At some point, I’d exercise. Maybe I’d go to the gym, pushing myself hard in the way that only young adults can, hiding from the heat in the air-conditioned fitness complex. Or I’d go for long runs in the swampy heat of the DC/NoVa summer, threading through the suburban side streets between my house and the high school I had attended. Over rolling hills, past churches, down sidewalk-less black streets. I had a plastic digital watch that would beep and provide a pace.

I would drive to the video store and swap watched VHS tapes for new ones. The car’s steering wheel would be almost too hot to grab. I would blast the AC with the sunroof cracked, music playing as I drove through the McLean streets.

My friends would call. Let’s hang out. Or go on a date. I had a few young women I saw sporadically. I went to the movies a staggering 35 times. But I remember that I really just wanted to stay home, writing and recording songs. I didn’t drink alcohol in those days either, so I had plenty of energy and focus.

Each night I went downstairs to my makeshift studio space, I would finish a whole song. I quickly decided this record would have a theme or a concept, and that concept would be the very summer I was living. I wrote about myself as a character, and lived my life as the character I was writing about. I thought of a Laurie Anderson quote: “This is the time, and this is the record of the time”. Those ideas began to inform the record, and once I had a few songs done, it helped guide me to finish the rest.

I had written songs before, but the summer of 1990 saw me taking things to a new level. Melodies became more intricate. Chord progressions evolved. There were bridges. I even put guitar solos on many tracks, as I had learned the unified neck and wanted to push myself.

I spent nearly the entire month of July living in Tokyo. I had planned to spend the summer in Taiwan teaching English, all arranged by my friend Andrew. But days before our planned departure, all the plans came apart. My parents, anxious to have me gone (and perhaps for me to have some kind of adventure) insisted I had to go somewhere. Some frantic phone calls later, and I was on a plane to Tokyo, with one suitcase, a guitar, and about $500.

The full story of my Tokyo adventures is best left for some other time. I did take a cassette of my rough mixes with me, which I promptly lost at a nightclub dancing with some girls I met. Most days I spent some time writing songs and practicing guitar.

I returned to the USA and again, the house was mine alone. I returned to my work plan. I went to the movies. Once or twice I went into DC to hang with my friends there. Had a few memorable nights at Poseurs, my favorite dance club (where, underage, my admittance was never guaranteed). One special night in Georgetown where a woman asked me to dance.

All of those feelings and experiences went into the record. There were songs about people I knew, coded and secret. There were songs where I got weird, adding strange sounds or switching time signatures. I tried different types of guitar orchestration. One song was an e-bow orchestra. Others used no chords. On the title track, I played a spiral pattern on the neck, and thrilled at how perfectly it fit, as did using a 3-bar phrase instead of a typical 4-bar phrase for some sections.

Listening to the record today, it is rather amateurish. The mixing is terrible. The vocals are wobbly. The guitar playing is rudimentary. But the record still has a unity and consistency. It sounds like an album, not just a bunch of songs. It tells a story, and it is very much the story of that summer.

It was a true DIY project -- I wrote, played, mixed, and recorded every note. Every song was a “real song” -- fully developed, with melodies, chords, lyrics, and ideas. Each was part of a larger whole. Sequenced carefully, varying in tempo and feel.

As noted in the 2000 MP3.com reissue, these songs "haven't held up all that well over the years, but they do mark an important step in my development as a songwriter. At the time, I was very proud of this work." Even if nobody else listened to it, liked it, or understood why I made it, or what it meant to me. I knew I could make records myself, and I knew that I absolutely loved doing it.

I am much better at music now -- better at writing songs, recording, playing guitar, singing. But no matter how good I get, and how satisfied I am with my work, none of it will compare to how accomplished, successful, and excited I felt at the end of the zero summer of 1990.

I think about that summer often. I realize that in many ways, I have tried to re-create pieces of that total experience at various points in my life. 2020, the summer of the virus, is one example. One could look at my upcoming “Paper Life” record as a kind of answer to “Zero Summer Game”, though it was not directly intended as such.

Not long ago, I dreamed I was back there, running through the neighborhood at night. I can feel the hot, sticky, evening air evaporate as I slide open the glass door at the back of the house and walk into the air conditioning.

A few times, I have driven back through those streets, wondering at how far I have come. I roll through the old neighborhood, peering down the hill at the house I lived in for a brief time.

|

Remains of the original paste-up used for the inside cover of the original cassette release of "Zero Summer Game", taken not long after I finished the project. Polaroid(!) photograph by Joseph Kirk.

|